Košík

0

x

Produkty

(prázdný)

Žádné díla

Bude determinováno

Dopravné a balné

0 Kč

Celkem

Produkt byl úspěšně přidán do nákupního košíku

Počet

Celkem

0 ks zboží.

1 dílo v košíku.

Za díla:

Doručení a balné:

Bude determinováno

Celkem

Kategorie

- grafiky/tisky

- obrazy

- kresby

- plakáty

- fotografie

- exlibris

- bibliofilie

- knihy/katalogy

- starožitnosti

- sochy/plastiky

- sklo

-

Hnutí

- abstrakce

- art-deco

- čs.avantgarda/moderna

- expresionismus

- fauvismus

- impresionismus

- kubismus

- naivní umění

- op-art

- poetismus

- pop-art

- realismus

- secese

- sociální kritika

- soudobá tvorba

- surrealismus

- světová avantgarda/moderna

- Škola prof. Albína Brunovského

- Škola prof. Zdeňka Sklenáře

- Škola prof.Julia Mařáka - mařákovci

- Žánr

- Zprávy/NEWS

- Doporučujeme

Nová díla

-

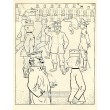

Zpívající ptáček velký, opus 725a

5 203 Kč -

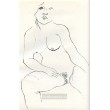

Ňadro s optikou

2 178 Kč -

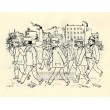

Ptáček v oblacích

1 452 Kč

-

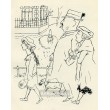

Psi se o kost hryzou, vezmi kost a přestanou (Česká přísloví)

290 Kč -80% 1 452 Kč

Hnutí

- abstrakce

- art-deco

- čs.avantgarda/moderna

- expresionismus

- fauvismus

- impresionismus

- kubismus

- naivní umění

- op-art

- poetismus

- pop-art

- realismus

- secese

- sociální kritika

- soudobá tvorba

- surrealismus

- světová avantgarda/moderna

- Škola prof. Albína Brunovského

- Škola prof. Zdeňka Sklenáře

- Škola prof.Julia Mařáka - mařákovci

Žánr

NEJŽÁDANĚJŠÍ UMĚLCI

- Anderle Jiří

- Augustovič Peter

- Benca Igor

- Beneš Karel

- Bím Tomáš

- Born Adolf

- Brun Robert

- Brunovský Albín

- Boštík Václav

- Bouda Cyril

- Bouda Jiří

- Braque Georges

- Brázda Jiří

- Buffet Bernard

- Cézanne Paul

- Čapek Josef

- Čápová Hana

- Dalí Salvador

- Demel Karel

- Dudek Josef

- Dufy Raoul

- Effel Jean

- Felix Karol

- Filla Emil

- Giacometti Alberto

- Grosz George

- Chagall Marc

- Istler Josef

- Janeček Ota

- Jiřincová Ludmila

- Kandinsky Wassily

- Kĺúčik Peter

- Komárek Vladimír

- Kulhánek Oldřich

- Kupka František

- Lada Josef

- Lhoták Kamil

- Matisse Henri

- Miró Joan

- Mucha Alfons

- Muzika František

- Picasso Pablo

- Pileček Jindřich

- Reynek Bohuslav

- Sukdolák Pavel

- Suchánek Vladimír

- Svolinský Karel

- Šíma Josef

- Špála Václav

- Švabinský Max

- Švengsbír Jiří

- Tichý František

- Toulouse-Lautrec Henri de

- Toyen

- Trnka Jiří

- Váchal Josef

- Vik Karel

- Warhol Andy

- Zábranský Vlastimil

- Zoubek Olbram

- Zrzavý Jan

Seznam děl umělce Grosz George

Německo: Vytvarné umění žije od poč. XX. stol. na předpokladech dobytých koncem XIX. stol. v zápase impresionismu proti úzkým obzorům, z nichž rostlo a které posilovalo "Heimatkunst". Až do poválečných let připadá vedoucí úkol malířství jako nejpružnější

Německo: Vytvarné umění žije od poč. XX. stol. na předpokladech dobytých koncem XIX. stol. v zápase impresionismu proti úzkým obzorům, z nichž rostlo a které posilovalo "Heimatkunst". Až do poválečných let připadá vedoucí úkol malířství jako nejpružnějšímu nástroji subjektivismu, teprve po válce za únavy vítězného expresionismu získává vedení věcnější architektura.

Malířství navázalo v impresionismu spojení se západem a vybojovalo pro budoucí tendence právo na individuální svobodu. Impresionismus vstupuje vítězně do nového století a žije plným životem ještě v době, kdy se stanou nové tendence kolektivní a generační otázkou. Ve svém čelném představiteli Maxi Liebermannovi (+1934) dočká se dokonce nastolení politické diktatury (1933), která jednak rozptýlí představitele expresionismu a zbavujíc svým tlakem umění individuální svobody, postaví je před úkol kolektivní služby. Začátek XX. stol. netvoří uměleckou hranici, umění tohoto věku přes všechny názorové rozdíly je pokračováním individualistické periody zahájené vítězstvím impresionismu a zastavené nastolením diktatury. Koncem XIX. stol. objevují se první stopy, jež vedou k expresionismu. Tato smíšená doba trvá až do utvoření prvních expresionistických skupin (drážďanská Die Brücke kolem r. 1904, mnichovská skupina Blaue Reiter 1911). Neoceňujíce těsnou souvislost [Německo]-a se západem, kde nastal odklon od zrakové formy dříve, kladou něm. historikové rodokmen expresionismu do díla švýcarského Němce Ferdinanda Hodlera (1853-1918), jehož úlohu srovnávají s posláním P. Cézanna. Hodler se odchýlil r. 1890 od optické zkušenosti k figurálním komposicím, které jsou neseny nejen zdůrazněným lineárním rytmem, ale opírají se také o tradiční alegorii a omezují barvu na kolorit (fresky v Jeně r. 1908). Vedle Hodlera, který zdůraznil grafickou stránku obrazu a projevil touhu po monumentalitě, vypadá E. Munch jako hotový expresionista. V [Německo]-u působil od r. 1892, kdy po prvé vystavoval v Berlíně, a souborem obrazů na výstavě berlínské Secesse z r. 1902, visionářskou grafikou i podobiznami přímo dotváří expresionismus. R. 1907 vrací se Munch definitivně do Norska. Základy expresionismu netvořili jen tito protichůdci zrakové formy obrazu, expresionistická tendence, jež se zdá být přímo složkou něm. výtvarného smyslu, projevila se i v impredionismu a dávala mu lokální barvu. U Liebermanna, nejbližšího západnímu cítění, nezmizela linie, ale ve spolupráci se štětcovým rukopisem přesahuje zejména v podobiznách meze zrakového dojmu. Ještě dále jde Lowis Corinth (1850-1925). Vitální vztah ke skutečnosti, který se projevuje prudkým rukopisem štětce, dospívá zde k patosu a patosem k spirituálním polohám. Obrazy, jako je portret Bernta Grönvalda, stojí na pokraji expresionismu. Vedle domácích předpokladů působily i západní vlivy. Pavla Modersohnová (1876-1907) dotvoří se z Gauguinova vlivu k vlastnímu výrazu, v němž se viděná skutečnost interpretovaná liniemi a plochami mění v subjektivní visi, které chybí do expresionismu jen patos. Bezprostředními předchůdci a pak i nositeli nové tendence je už Christian Rohlfs (*1849) a Emil Nolde (*1867), který se už stal členem drážďanské skupiny "Die Brücke". Expresionismus jako obdobná tendence ve Francii a jinde vznikl z reakce na zrakovou formu obrazu, kterou přivedl impresionismus k maximální živosti. Na rozdíl od francouzského fauvismu, jemuž se podobá malířskou metodou, je expresionismus v [Německo]-u mystičtější a obsahovější, nespokojuje se kultem čisté výtvarnosti a dekorativním působením obrazu. V tom směru je bližší van Goghovi a oné náladě, z níž vznikla u Gauguina snaha obrodit symbol a u M. Denise snaha obnovit náboženské umění. To platí stejně o skupině drážďanských jako mnichovských expresionistů. Mezi oběma křídly není rozdílu v cíli, ale v prostředcích. Drážďanští expresionisté M. Pechstein (*1881), E. Heckel (*1883), E. L. Kirchner (*1880), E. Nolde, K. Schmidt-Rottluff (*1884) jsou předmětnější. Znásilňují optickou tvářnost skutečnosti lineární i barevnou deformací, aby dali předmětu symbolickou platnost a schopnost tlumočit extatický nebo patetický lyrismus, ale předmětu se nevzdávají. V deformaci uplatňují se vlivy západního malířství, barevný patos van Goghův, Gauguinův exotismus, vlivy primitivního umění a zejména černošské plastiky, kterou horlivě propagoval K. Schmidt-Rottluff. Drážďanská skupina se rozešla r. 1913, když založil Pechstein r. 1911 Novou berlínskou secesi. Mnichovští expresionisté, kteří vytvořili skupinu Blaue Reiter, Rusové V. Kandinskij (*1867), A. Javlenskij (*1861) a z Němců Franz Marc (1880-1916), A. Macke (1887-1917) a Paul Klee (*1879), více nebo méně odmítají zprostředkující úlohu předmětu a snaží se budit emoci přímo výtvarnými prostředky. Teoretikem a vůdcem tohoto hnutí byl V. Kandinskij, který postuluje malířství jako čistou hudbu barev v knize Das Geistige in der Kunst z roku 1912. Kandinskij došel k bezpředmětné malbě, jejíž sdělitelnost je sporná a která působí ornamentálně. Tak daleko nešel z ostatních nikdo. Silnou osobností byl F. Marc, který padl ve válce. Paul Klee rozvinul později křehký a subjektivní lyrismus snových stavů až na pokraj nadrealismu, využívaje záměrně poznání dětské kresby i poučení z umění primitivů. Vedle tohoto rafinovaného umění znamená Macke přechod ke kubismu, který měl v [Německo]-u vždycky jen nepřímou ozvěnu. Z toho se nevymyká ani Lionel Feininger (*1871), který uplatnil geometrisaci na městských motivech, jež měnil v krystalové útvary podobné zhusta jevištní architektuře. Abstraktní tendence zbavená expresionistických záměrů uplatní se teprve po válce vlivem architektury v době výtvarného skepticismu a bude vnucovat malířství i sochařství ryze ornamentální poslání (Bauhaus).

Válka znamená velikou proměnu, ale nikoliv pád expresionismu. Hnutí, jež v prvním rozmachu usilovalo o obnovu náboženské malby (Nolde), unikalo idyle exotismem (E. Heckel), násilným přepisem skutečnosti (Kirchner, Schmidt-Rottluff) nebo směřováním k čisté výtvarnosti (mnichovská skupina), bylo jen uměleckou otázkou. Koncem války a po válce stává se tato násilná interpretace výrazem národního pesimismu, který zrál v utrpení války a dozrál porážkou. Původní mysticismus expresionismu čerpá z tohoto ovzduší pesimismus a v souhlase s dobou stává se výrazem kolektivní nálady a zároveň oficiálním uměním. Tato situace přináší velký rozmach zejména grafice. Grafická složka tvoří vůbec podstatný díl německého výtvarného smyslu. Nepotlačilo ji ani vítězství barvy v impresionismu, ba lze říci, že uchovávala smysl pro obsah (Käthe Kollwitzová), nebo chystala půdu deformaci v karikatuře (Th. Th. Heine s časopisem Simplicissimus). Už v předválečném expresionismu byla grafika posílena, ale po válce se jí dostává přímo vedoucího postavení. Nejnázornější doklad podává Georg Grosz (*1893). Z jeho obrazu společnosti vysoké buržoasie, kterou ukázal v jejím morálním bahně, byl chápán především apokalyptický pesimismus. K sociální víře došel Grosz ostatně teprve vývojem, jehož východisko je v dadaismu. Typickým představitelem této doby je M. Beckmann (*1884), který se dívá v ekstatickém pesimismu na lidi jako na loutky a masky podivného karnevalu. V této době stává se [Německo] vlastí expresionismu a po otevření hranic navazuje se styk se všemi experimenty. Oskar Kokoschka (*1886), jehož expresionismus vyrostl v prostředí secesní Vídně, stal se profesorem v Drážďanech. Brzy po r. 1920 přivodí dlouho trvající stav ekstatického pesimismu únavu a vzbudí snahu o únik, která se projevuje v mezích i mimo meze expresionismu. Do expresionismu proniká sociální tendence, která aktualisuje sociální realismus K. Kollwitzové (*1867) a zároveň vytvoří most k nové věcnosti (O. Dix *1891). Usiluje se o formální uklidnění obrazu, v čemž lze hledat matnou ozvěnu neoklasicismu (C. Hofer, *1878), i cestu k nové věcnosti. Ale ani zesílení této tendence, jež postuluje obnovu objektivity a kterou representují A. Kanoldt (*1886), O. Dix, K. Meuse (*1886), G. Schrimpf (*1889), a v malířských dílech i Grosz, nemění nic na pestrosti individuálních i směrových rozdílů. Až do vzniku diktatury žijí vedle sebe tendence od impresionismu až k nadrealismu, jemuž dalo [Německo] Maxe Ernsta.

Sochařství, jež bylo tradičnější i v době impresionismu, šlo mnohem klidnější cestou a přijímalo spíše podněty z malířství nebo vliv francouzské plastiky. Lineární stylisace a působení tradice, která má větší sílu v plastice vzdorující věcností subjektivismu, zabránily vytvoření zrakové formy v sochařství. Příhodná chvíle přichází německému výtvarnému smyslu teprve tehdy, kde se obnovuje tvar určený především hmatem. To je případ G. Kolbeho (*1877), H. Hallera (*1881) i Ernesta de Fiori (*1881). Expresionismus, který měl předchůdce v lineární stylisaci (F. Metzner 1870-1919), projeví se v prodloužených tvarech u W. Lehmbrucka (1881-1919), ale nalezne vlastního představitele teprve v Ernstu Barlachovi (*1870), který si vytvořil svůj rustikální mysticismus životní tíhy a hrůzy r. 1906 po své cestě do Ruska. Expresionistického původu bylo i hledání opory v černošské plastice u R. Bellinga (*1886), ale vyústilo k formálnějším výsledkům a k snaze změnit sochu v soběstačnou věc. Velikou proměnu přinesla výtvarnému umění diktatura, která vykládá novou věcnost - původně tendenci sociálního přízvuku - jako konec subjektivismu a podrobení se normě a totalitě. (Viz též přílohu u hesla * Expresionismus).

Lit.: F. Kovárna, Současné malířství 1930; Waldmann, La peinture allemande contemporaine 1930; C. Einstein, Die Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts 1928; R. Hamann, Geschichte der Kunst 1933; Alfred Kuhn, Die neuere Plastik 1922. -rna.

(In: Ottův slovník naučný nové doby)

* * * * * Grosz George, *1893, něm. malíř a grafik, jeden z nejříznějších karikaturistů souč. doby. Vyšel z individualistického anarchismu, na sklonku války účastnil se počátků berlín. destruktivního hnutí * Dada, po válce se stal vlivem sociálního uvědomění nelítostným uměl. soudcem vládnoucí buržoasie v Něm. Jeho karikatura nemá v sobě veselosti, chce býti jen účinným prostředkem třídního boje. Karikuje s oblibou typy z prostředí velkokapitalistického, buržoasního i militaristického a staví jejich rozmařilý život do příkrého kontrastu s bídou chudiny a váleč. mrzáků. Se statečnou bezohledností obnažuje zvl. surovost nyn. života sexuálního a k zvýšení drastického účinu neváhá někdy přejímati pojetí obscenních kreseb pissoirových. Prostým podáním, jehož vzor je v dět. kresbách, dopracoval se charakteristické zkratky, hojně i u nás napodobované. Olejomalby a montáže, v nichž usiluje někdy o souč. zachycení tempa a mnohotvárnosti velkoměst. života, jeví jednak vlivy futurismu, jednak i jistou příbuznost s Ensorem a se snahami surréalistů. - Pro politický, zejm. antimilitaristický obsah karikatur byl [Grosz George] několikrát před soudem. 1932 byl z rozhodnutí studentů zvolen doc. kreslení na akademii v New Yorku. - Alba grafiky a karikatur: Erste Grosz-Mappe 1916, Kleine Grosz-Mappe 1917, Haifische 1920, Mit Pinsel und Schere (montáže 1920), Die Räuber 1922, Gott mit uns; Ecce homo 1923, Das Gesicht der herrschenden Klasse; Die Gezeichneten; Das neue Gesicht der herrsch. Klasse a j. - Obrazy: Německo, zimní pohádka 1918, Zatmění slunce 1925, portrety matky, spis. M. Herrmanna a W. Mehringa, boxera Schmelinga a j. Pro Piscatora inscenoval Haškova Švejka v Berlíně a nakreslil k němu řízné karikatury, které byly při představení promítány. - Srv.: Wolfradt W., George [Grosz George] 1921, Mynona, George [Grosz George] 1922, Italo Tavolato, Georg [Grosz George] 1924, Marcel Ray, George [Grosz George] 1927. Hs.

(In: Ottův slovník naučný nové doby)

1893

26. Juli: Georg Gross wird in Berlin als Sohn eines Gastwirts geboren.

1909

Aufnahme an der Königlichen Kunstakademie Dresden.

1912-1917

Er besucht mit Unterbrechungen die Kunstgewerbeschule in Berlin als Schüler von Emil Orlik (1870-1932).

1914

Um der allgemeinen Einberufung aufgrund der Wehrpflicht zuvorzukommen, meldet er sich bei Ausbruch des Ersten Weltkriegs als Freiwilliger bei einem Grenadier-Regiment in Berlin.

1915

11. Mai: Nach einer Operation einer Stirnhöhlenvereiterung wird er als dienstuntauglich entlassen.

1916

Namensänderung in George Grosz.

Mit der Veröffentlichung von Zeichnungen in der Monatsschrift "Neue Jugend" und in Theodor Däublers (1876-1934) literarischem Magazin "Die weissen Blätter" wird Grosz in der Kunstszene bekannt.

1917

4. Januar: Grosz wird als Landsturmpflichtiger erneut eingezogen.

20. Mai: Nach Aufenthalten in einem Lazarett für Schwerverletzte und einer Nervenheilanstalt wird er als dauernd kriegsunbrauchbar entlassen. Die "Kleine Grosz-Mappe" erscheint im Berliner Malik-Verlag.

1919

Verhaftung während des Spartakusaufstands. Aufgrund eines falschen Ausweises kann er jedoch entkommen und untertauchen.

Grosz wird Mitglied der Kommunistischen Partei Deutschlands (KPD).

1920

Erste Einzelausstellung in der Münchener Galerie "Neue Kunst Hans Goltz".

Mitveranstalter der "Ersten Internationalen Dada-Messe" in Berlin.

Heirat mit Eva Peter.

Grosz entwickelt sich zum Chronisten und Kritiker seiner Zeit. Vor allem der Militarismus und das konservativ-reaktionäre Bürgertum der Weimarer Republik sind Hauptthemen vieler seiner Gemälde und Mappenwerke.

1921

Anklage und Verurteilung zu einer Geldstrafe von 300 Mark wegen Beleidigung der Reichswehr. Das Gericht verfügt ferner die Vernichtung der Mappe "Gott mit uns".

1922

Fünfmonatige Rußlandreise mit Martin Andersen Nexö (1869-1954). Treffen mit Wladimir I. Lenin und Leo D. Trotzki.

1923

Die Erfahrungen in Rußland bestärken ihn in seinem Mißtrauen gegen jede Form der diktatorischen Obrigkeit und veranlassen ihn zum Austritt aus der KPD.

Aus der Mappe "Ecce Homo" werden mehrere Zeichnungen beschlagnahmt.

1924

Grosz und weitere sieben Küstler geben die Mappe "Hunger" zugunsten der "Internationalen Hungerhife" heraus.

1926

Zusammen mit Maximilian Harden, Max Pechstein und Erwin Piscator gründet Grosz den "Club 1926 e.V.", eine Gesellschaft für Politik, Wissenschaft und Kunst.

1928

Grosz fertigt 300 Zeichnungen für einen Trickfilm an, der während der Aufführung des Stücks "Die Abenteuer des braven Soldaten Schwejk" von Jaroslav Hašek (1883-1923) in Berlin zu sehen ist. Einige Blätter der gleichzeitig erschienenen Schwejk-Mappe "Hintergrund" führen zu einer Anzeige wegen Gotteslästerung.

1932

Mehrmonatiger Aufenthalt in New York.

1933

12. Januar: Grosz emigriert nach New York.

Gleich nach der Machtübernahme der Nationalsozialisten werden seine Wohnung und sein Atelier gestürmt.

1934-1936

Grosz arbeitet für amerikanische Satirezeitschriften.

1937

Die Nationalsozialisten diffamieren Grosz' Werke als "entartete Kunst" und beschlagnahmen 285 von ihnen aus deutschen Museen. Seine Bilder werden in der Ausstellung "Entartete Kunst" gezeigt.

1938

Grosz erhält die amerikanische Staatsbürgerschaft.

1941

Das Museum of Modern Art, New York, zeigt eine Grosz-Retrospektive.

1945

Beteiligung an der Ausstellung "Painting in the United States 1945" in Pittsburgh, auf der 350 Gemälde von 350 Künstlern gezeigt werden.

Grosz leidet unter depressiven Stimmungen, die zunehmenden Alkoholkonsum zur Folge haben.

1946

Grosz veröffentlicht seine Autobiographie "A Little Yes and a Big No" im Verlag Dial Press, New York.

1947-1953

Mehrere Ausstellungen in amerikanischen Museen.

1951

Erste Deutschlandreise nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg.

1954

Grosz wird Mitglied der hochangesehenen "American Academy of Arts and Letters".

1955

Grosz' Autobiographie erscheint als "Ein kleines Ja und ein großes Nein" im Hamburger Rowohlt Verlag.

1958

Die Berliner Akademie der Künste wählt ihn zum außerordentlichen Mitglied der Abteilung "Bildende Kunst".

1959

5. Juli: George Grosz stirbt kurz nach seiner Übersiedlung nach Berlin an den Folgen einer durchzechten Nacht. * * * * * "Grosz considered himself a propagandist of the social revolution. He not only depicted victims of the catastrophe of the First World War - the disabled, crippled, and mutilated - he also portrayed the collapse of capitalist society and its values. His wartime line drawings show him to be a master of caricature. In a 1925 portfolio of prints Grosz ridiculed Hitler by dressing him in a bearskin, a swastika tattooed on his left arm. Until 1927 he also painted large allegorical paintings that focused on the plight of Germany; Count Harry Kessler, a leading intellectual and collector, called these 'modern history pictures.'

"Grosz was called by some the 'bright-red art executioner,' and indeed his political radicalism was well known. He had joined the German Communist party in 1922. Although a trip to Russia later that year disillusioned him, he continued to work with [radical publisher] Malik Verlag. Feeling out of step with Russia's politics, Grosz resigned from the party in 1923, but the next year he became a leader of Berlin's Rote Gruppe (Red group), an organization of revolutionary Communist artists that prefigured the Assoziation revolutionarer bildender Kunstler Deutschlands (ASSO, Association of revolutionary visual artists of Germany).

"By 1929 the political climate in Germany had shifted to the right, and, at best, Grosz's work was considered anachronistic. The periodical Kunst und Kunstler (Art and artists) commented...: 'Dix's Barrikade (Barricade) and Grosz's Wintermarchen (Winter tale) are now curiosities that only have a place in a wax museum, commemorating the revolutionary time. One doesn't make art with conviction alone.' In a somewhat more positive light, Grosz was described as a historical figure in the periodical Eulenspiegel in 1931: 'No other German artist so consciously used art as a weapon in the fight of the German workers during 1919 to 1923 as did George Grosz. He is one of the first artists in Germany who consciously placed art in the service of society. His drawings...are worthwhile not only in the present but also are documents of proletarian revolutionary art.' These comments were more indicative of the magazine's editorial stance than the tenor of the times, however. More in keeping with popular sentiment, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration (German art and decoration) described Grosz as one-sided and pathological, 'too obstinate, too fanatical, too hostile to be a descendant of Daumier .' Although according to the magazine's art writer he was a master of form, his social point of view was wrongly chosen.

"Grosz's reputation as a political activist and deflator of German greatness was no secret. Menacing portents and premonitions of disaster began to haunt him. A studio assistant appeared in a brown shirt one day and warned him to be careful; a threatening note calling him a Jew was found beside his easel. A nightmare he recounted in his autobiography ended with a friend shouting at him 'Why don't you go to America?' When in the spring of 1932 a cable arrived from the Art Students League in New York, inviting him to teach there during the summer, he accepted immediately. After a short return to Germany, where he was advised that his apartment and studio had been searched by the Gestapo, who were looking for him, the artist emigrated in January 1933. He became an American citizen in 1938.

"In the meantime Grosz was among the defamed artists whose works had been included in two Schandausstellungen (abomination exhibitions) in Mannheim and Stuttgart in 1933 In a letter of July 21, 1933, Grosz wrote that he was secretly pleased and proud about this turn of events, because his inclusion in these exhibitions substantiated the fact that his art had a purpose, that it was true 9 The polemical articles about modern art, "art on the edge of insanity" as the official Nazi newspaper, the Volkischer Beobachter called it, also regularly included Grosz, with particular attention paid to his portraiture. A portrait of Max Hermann-Neisse, later to appear in the exhibition Entartete Kunst, was singled out for the "degenerate loathsomeness of the subject." A total of 285 of Grosz's works were collected from German institutions; five paintings, two watercolors, and thirteen graphic works were included in Entartete Kunst.

"Grosz participated in an anti-Axis demonstration in New York in 1940 and revealed his reaction to the Führer in an interview with Rundfunk Radio in 1958:

"When Hitler came, the feeling came over me like that of a boxer; I felt as if I had lost. All our efforts were for nothing."

"Grosz returned to Germany permanently in 1958, somewhat disillusioned with his American interlude. He had wanted a new beginning and had tried to deny his political and artistic past, but he was appreciated in America primarily as a satirist, and the work from the period after the First World War was perceived as his best. The biting commentary that marked this early work was that of a misanthropic pessimist, not what he had become: an optimist infatuated with the United States. Grosz was unable to understand the American psyche to the degree that he had the German, and he returned to his homeland in an attempt to regain the momentum he had lost. He died in Berlin in an accident six weeks after his return."

- From Stephanie Barron, "Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany" In: http://www.artchive.com/artchive/G/grosz.html * * * * * Born 26 July 1893 Berlin. Painter, writer and caricaturist. Studied at the Dresden and Berlin academies. Contributed to satirical periodicals. Came to the Berlin dada movement in 1918. Edited the periodicals "Die Pleite" ("Bankruptcy") together with Wieland Herzfelde; "Jeder sein eigener Fussball" ("Everyman his own Football") with Franz Jung; and "Der blutige Ernst" ("In Bloody Earnest"), with Carl Einstein. On his dada period he wrote in his book "Art In Danger": "Civilian again, I experienced in Berlin the rudimentary beginnings of the dada movement, the start of which coincided with the 'swede' period of malnutrition. The roots of this German dada movement were to be found in the recognation that it was perfectly crazy to believe that the spirit, or anything spiritual ruled the world. Dadaism was the only significant artistic movement in Germany for decades. Dadaism was no artificially fostered movement but an organic product, at its origin a reaction to the cloudlike ramblings of so-called sacred art. Dadaism forced artists to declare openly their position .. . What did the dadaists do? They said that it did not matter whether a man blew a 'raspberry' or recited a sonnet by Petrarca or Shakespeare or Rilke, whether he gilded jack-boot heels or carved statues of the Virgin. Shooting went on regardless, profiteering went on regardless, people would go on starving regardless, lies would always be told regardless—what was the good of art anyway? In those days we saw the mad final excrescences of the ruling order of society, and burst out laughing. We did not yet see that there was a system behind all this madness." George Grosz was the most pitiless caricaturist of the German bourgeoisie and of German militarism. In 1925 he approached that type of realism designated as "new matter-of-factness". In the U. S. A., where he went in 1932, his pictures assumed romantic, idyllic overtones. Looking back on it all, he wrote in his autobiography "A Little Yes And A Big No": "Artistically speaking we were 'dadaists' in those days. If that meant anything it was a disquiet, a dissatisfaction, a delight in mockery, that had all been fermenting a long time already. Every defeat, every upheaval gives birth to such movements. In another period we might have been flagellants . . . Huelsenbeck imported dada to Berlin, and it assumed immediately political features. The aesthetical side was preserved, but got more and more supplanted by a kind of anarchist-nihilistic politics, chiefly propounded by the writer, Franz Jung." In: http://www.peak.org/~dadaist/English/Graphics/grosz.html * * * * * 1893 Born: Berlin, Germany (July 26)

1908 Expelled from grammar school

1911 Königliche Kunstakademie. Dresden, Germany.

1912 College of Arts and Crafts. Berlin, Germany

1913 Trains at Colarossi's Studio. Paris, France.

1954 Elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters

1958 Elected to the Academy of Fine Arts of Germany

1959 Died: Berlin, Germany

Selected Exhibitions

1998 George Grosz-Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler, Galerie St. Etienne New York

1997 The Berlin of George Grosz: Drawings, Watercolors and Prints 1912-1930, Royal Academy of Arts London, England

1997 The New Objectivity, Galerie St. Etienne New York

1993 Art & Politics in Weimar Germany, Galerie St. Etienne New York

1986 German Realist Drawings of the 1920's, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum New York, NY

1985 German Art of the 20th Century, Royal Academy of Art London, England

1980 Expressionism: A German Intuition, S.R. Guggenheim Museum New York, NY

1978 Cityscape 1910-39: Urban themes in American, German and British art, Royal Academy of Arts London, England

1975 George Grosz, Leben und Werk, Kunstverein Hamburg

1959 Hecksher Museum, Hecksher Museum Huntington, NY

1954 Retrospective Exhibition, Whitney Museum of American Art New York, NY

1952 Dallas Museum of Fine Art, Dallas Museum of Fine Art Dallas, TX

1950 The Institute of Art, The Institute of Art Cleveland, OH

1948 The Stickmen, Associated American Artists New York, NY

1946 A Piece of My World in a World Without Peace, Associated American Artists New York, NY

1945 Associated American Artists, Associated American Artists Chicago, IL

1944 Denver Art Museum, Denver Art Museum Denver, CO

1943 Museum of Art, Museum of Art Baltimore, MD

1941 Associated American Artists, Associated American Artists New York, NY

1941 Traveling Retrospective Exhibition, Museum of Modern Art New York, NY

1939 Walker Gallery, Walker Gallery New York, NY

1938 Art Institute, Art Institute Chicago, IL

1937 Degenerate Art, Munich, Germany

1933 New York, NY

1933 Chicago, IL

1933 Philadelphia, PA

1932 Art Institute, Art Institute Milwaukee, WI

1931 Berlin, Germany

1931 New York, NY

1931 Chicago, IL

1930 Venice Biennale, Venice Biennale Venice, Italy

1930 Kunsthaus Zurich Zurich, Switzerland

1927 Flechtheim Gallery, Oils, Flechtheim Gallery Berlin, Germany

1925 Neue Sachlichkeit, Städtische Kunsthalle Mannheim, Germany

1920 First International Dada Fair, Berlin, Germany

1920 First One Man Exhibition, Hans Goltz Munich, Germany

In: http://www.artnet.com/artist/7477/george-grosz.html * * * * *

Grosz, George (1893-1959), American Expressionist painter and illustrator, of German birth. Born in Berlin, he studied art at the Royal Academy, Dresden, the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin, and the Académie Colarossi, Paris, and served in the army in World War I. He is known for his fiercely satirical drawings and caricatures. Collections of these drawings, concerned with conditions in Germany at the end of World War I, appeared in Ecce homo (Behold the Man, 1923) and Das Gesicht der Herrschenden Klasse (The Face of the Ruling Class, 1921). Republican Automatons (1920) reflects his view of modern man as a machine.

An uncompromising opponent of militarism and National Socialism, Grosz was one of the first German artists to attack Adolf Hitler. Grosz went to the United States in 1932 and became an American citizen in 1938. From about 1936 he began to work also in oils and turned to less biting themes, depicting nudes, still lifes and street scenes. With the approach of World War II his art became increasingly despairing. Recognized as one of the most brilliant draughtsmen of his time, Grosz was also well known as a teacher. An account of his experiences as an artist appears in his autobiography A Little Yes and a Big No (1946). He was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1954, and in 1959, shortly before his death, resettled in Berlin.

In: MS Encarta

Zobrazit

Malířství navázalo v impresionismu spojení se západem a vybojovalo pro budoucí tendence právo na individuální svobodu. Impresionismus vstupuje vítězně do nového století a žije plným životem ještě v době, kdy se stanou nové tendence kolektivní a generační otázkou. Ve svém čelném představiteli Maxi Liebermannovi (+1934) dočká se dokonce nastolení politické diktatury (1933), která jednak rozptýlí představitele expresionismu a zbavujíc svým tlakem umění individuální svobody, postaví je před úkol kolektivní služby. Začátek XX. stol. netvoří uměleckou hranici, umění tohoto věku přes všechny názorové rozdíly je pokračováním individualistické periody zahájené vítězstvím impresionismu a zastavené nastolením diktatury. Koncem XIX. stol. objevují se první stopy, jež vedou k expresionismu. Tato smíšená doba trvá až do utvoření prvních expresionistických skupin (drážďanská Die Brücke kolem r. 1904, mnichovská skupina Blaue Reiter 1911). Neoceňujíce těsnou souvislost [Německo]-a se západem, kde nastal odklon od zrakové formy dříve, kladou něm. historikové rodokmen expresionismu do díla švýcarského Němce Ferdinanda Hodlera (1853-1918), jehož úlohu srovnávají s posláním P. Cézanna. Hodler se odchýlil r. 1890 od optické zkušenosti k figurálním komposicím, které jsou neseny nejen zdůrazněným lineárním rytmem, ale opírají se také o tradiční alegorii a omezují barvu na kolorit (fresky v Jeně r. 1908). Vedle Hodlera, který zdůraznil grafickou stránku obrazu a projevil touhu po monumentalitě, vypadá E. Munch jako hotový expresionista. V [Německo]-u působil od r. 1892, kdy po prvé vystavoval v Berlíně, a souborem obrazů na výstavě berlínské Secesse z r. 1902, visionářskou grafikou i podobiznami přímo dotváří expresionismus. R. 1907 vrací se Munch definitivně do Norska. Základy expresionismu netvořili jen tito protichůdci zrakové formy obrazu, expresionistická tendence, jež se zdá být přímo složkou něm. výtvarného smyslu, projevila se i v impredionismu a dávala mu lokální barvu. U Liebermanna, nejbližšího západnímu cítění, nezmizela linie, ale ve spolupráci se štětcovým rukopisem přesahuje zejména v podobiznách meze zrakového dojmu. Ještě dále jde Lowis Corinth (1850-1925). Vitální vztah ke skutečnosti, který se projevuje prudkým rukopisem štětce, dospívá zde k patosu a patosem k spirituálním polohám. Obrazy, jako je portret Bernta Grönvalda, stojí na pokraji expresionismu. Vedle domácích předpokladů působily i západní vlivy. Pavla Modersohnová (1876-1907) dotvoří se z Gauguinova vlivu k vlastnímu výrazu, v němž se viděná skutečnost interpretovaná liniemi a plochami mění v subjektivní visi, které chybí do expresionismu jen patos. Bezprostředními předchůdci a pak i nositeli nové tendence je už Christian Rohlfs (*1849) a Emil Nolde (*1867), který se už stal členem drážďanské skupiny "Die Brücke". Expresionismus jako obdobná tendence ve Francii a jinde vznikl z reakce na zrakovou formu obrazu, kterou přivedl impresionismus k maximální živosti. Na rozdíl od francouzského fauvismu, jemuž se podobá malířskou metodou, je expresionismus v [Německo]-u mystičtější a obsahovější, nespokojuje se kultem čisté výtvarnosti a dekorativním působením obrazu. V tom směru je bližší van Goghovi a oné náladě, z níž vznikla u Gauguina snaha obrodit symbol a u M. Denise snaha obnovit náboženské umění. To platí stejně o skupině drážďanských jako mnichovských expresionistů. Mezi oběma křídly není rozdílu v cíli, ale v prostředcích. Drážďanští expresionisté M. Pechstein (*1881), E. Heckel (*1883), E. L. Kirchner (*1880), E. Nolde, K. Schmidt-Rottluff (*1884) jsou předmětnější. Znásilňují optickou tvářnost skutečnosti lineární i barevnou deformací, aby dali předmětu symbolickou platnost a schopnost tlumočit extatický nebo patetický lyrismus, ale předmětu se nevzdávají. V deformaci uplatňují se vlivy západního malířství, barevný patos van Goghův, Gauguinův exotismus, vlivy primitivního umění a zejména černošské plastiky, kterou horlivě propagoval K. Schmidt-Rottluff. Drážďanská skupina se rozešla r. 1913, když založil Pechstein r. 1911 Novou berlínskou secesi. Mnichovští expresionisté, kteří vytvořili skupinu Blaue Reiter, Rusové V. Kandinskij (*1867), A. Javlenskij (*1861) a z Němců Franz Marc (1880-1916), A. Macke (1887-1917) a Paul Klee (*1879), více nebo méně odmítají zprostředkující úlohu předmětu a snaží se budit emoci přímo výtvarnými prostředky. Teoretikem a vůdcem tohoto hnutí byl V. Kandinskij, který postuluje malířství jako čistou hudbu barev v knize Das Geistige in der Kunst z roku 1912. Kandinskij došel k bezpředmětné malbě, jejíž sdělitelnost je sporná a která působí ornamentálně. Tak daleko nešel z ostatních nikdo. Silnou osobností byl F. Marc, který padl ve válce. Paul Klee rozvinul později křehký a subjektivní lyrismus snových stavů až na pokraj nadrealismu, využívaje záměrně poznání dětské kresby i poučení z umění primitivů. Vedle tohoto rafinovaného umění znamená Macke přechod ke kubismu, který měl v [Německo]-u vždycky jen nepřímou ozvěnu. Z toho se nevymyká ani Lionel Feininger (*1871), který uplatnil geometrisaci na městských motivech, jež měnil v krystalové útvary podobné zhusta jevištní architektuře. Abstraktní tendence zbavená expresionistických záměrů uplatní se teprve po válce vlivem architektury v době výtvarného skepticismu a bude vnucovat malířství i sochařství ryze ornamentální poslání (Bauhaus).

Válka znamená velikou proměnu, ale nikoliv pád expresionismu. Hnutí, jež v prvním rozmachu usilovalo o obnovu náboženské malby (Nolde), unikalo idyle exotismem (E. Heckel), násilným přepisem skutečnosti (Kirchner, Schmidt-Rottluff) nebo směřováním k čisté výtvarnosti (mnichovská skupina), bylo jen uměleckou otázkou. Koncem války a po válce stává se tato násilná interpretace výrazem národního pesimismu, který zrál v utrpení války a dozrál porážkou. Původní mysticismus expresionismu čerpá z tohoto ovzduší pesimismus a v souhlase s dobou stává se výrazem kolektivní nálady a zároveň oficiálním uměním. Tato situace přináší velký rozmach zejména grafice. Grafická složka tvoří vůbec podstatný díl německého výtvarného smyslu. Nepotlačilo ji ani vítězství barvy v impresionismu, ba lze říci, že uchovávala smysl pro obsah (Käthe Kollwitzová), nebo chystala půdu deformaci v karikatuře (Th. Th. Heine s časopisem Simplicissimus). Už v předválečném expresionismu byla grafika posílena, ale po válce se jí dostává přímo vedoucího postavení. Nejnázornější doklad podává Georg Grosz (*1893). Z jeho obrazu společnosti vysoké buržoasie, kterou ukázal v jejím morálním bahně, byl chápán především apokalyptický pesimismus. K sociální víře došel Grosz ostatně teprve vývojem, jehož východisko je v dadaismu. Typickým představitelem této doby je M. Beckmann (*1884), který se dívá v ekstatickém pesimismu na lidi jako na loutky a masky podivného karnevalu. V této době stává se [Německo] vlastí expresionismu a po otevření hranic navazuje se styk se všemi experimenty. Oskar Kokoschka (*1886), jehož expresionismus vyrostl v prostředí secesní Vídně, stal se profesorem v Drážďanech. Brzy po r. 1920 přivodí dlouho trvající stav ekstatického pesimismu únavu a vzbudí snahu o únik, která se projevuje v mezích i mimo meze expresionismu. Do expresionismu proniká sociální tendence, která aktualisuje sociální realismus K. Kollwitzové (*1867) a zároveň vytvoří most k nové věcnosti (O. Dix *1891). Usiluje se o formální uklidnění obrazu, v čemž lze hledat matnou ozvěnu neoklasicismu (C. Hofer, *1878), i cestu k nové věcnosti. Ale ani zesílení této tendence, jež postuluje obnovu objektivity a kterou representují A. Kanoldt (*1886), O. Dix, K. Meuse (*1886), G. Schrimpf (*1889), a v malířských dílech i Grosz, nemění nic na pestrosti individuálních i směrových rozdílů. Až do vzniku diktatury žijí vedle sebe tendence od impresionismu až k nadrealismu, jemuž dalo [Německo] Maxe Ernsta.

Sochařství, jež bylo tradičnější i v době impresionismu, šlo mnohem klidnější cestou a přijímalo spíše podněty z malířství nebo vliv francouzské plastiky. Lineární stylisace a působení tradice, která má větší sílu v plastice vzdorující věcností subjektivismu, zabránily vytvoření zrakové formy v sochařství. Příhodná chvíle přichází německému výtvarnému smyslu teprve tehdy, kde se obnovuje tvar určený především hmatem. To je případ G. Kolbeho (*1877), H. Hallera (*1881) i Ernesta de Fiori (*1881). Expresionismus, který měl předchůdce v lineární stylisaci (F. Metzner 1870-1919), projeví se v prodloužených tvarech u W. Lehmbrucka (1881-1919), ale nalezne vlastního představitele teprve v Ernstu Barlachovi (*1870), který si vytvořil svůj rustikální mysticismus životní tíhy a hrůzy r. 1906 po své cestě do Ruska. Expresionistického původu bylo i hledání opory v černošské plastice u R. Bellinga (*1886), ale vyústilo k formálnějším výsledkům a k snaze změnit sochu v soběstačnou věc. Velikou proměnu přinesla výtvarnému umění diktatura, která vykládá novou věcnost - původně tendenci sociálního přízvuku - jako konec subjektivismu a podrobení se normě a totalitě. (Viz též přílohu u hesla * Expresionismus).

Lit.: F. Kovárna, Současné malířství 1930; Waldmann, La peinture allemande contemporaine 1930; C. Einstein, Die Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts 1928; R. Hamann, Geschichte der Kunst 1933; Alfred Kuhn, Die neuere Plastik 1922. -rna.

(In: Ottův slovník naučný nové doby)

* * * * * Grosz George, *1893, něm. malíř a grafik, jeden z nejříznějších karikaturistů souč. doby. Vyšel z individualistického anarchismu, na sklonku války účastnil se počátků berlín. destruktivního hnutí * Dada, po válce se stal vlivem sociálního uvědomění nelítostným uměl. soudcem vládnoucí buržoasie v Něm. Jeho karikatura nemá v sobě veselosti, chce býti jen účinným prostředkem třídního boje. Karikuje s oblibou typy z prostředí velkokapitalistického, buržoasního i militaristického a staví jejich rozmařilý život do příkrého kontrastu s bídou chudiny a váleč. mrzáků. Se statečnou bezohledností obnažuje zvl. surovost nyn. života sexuálního a k zvýšení drastického účinu neváhá někdy přejímati pojetí obscenních kreseb pissoirových. Prostým podáním, jehož vzor je v dět. kresbách, dopracoval se charakteristické zkratky, hojně i u nás napodobované. Olejomalby a montáže, v nichž usiluje někdy o souč. zachycení tempa a mnohotvárnosti velkoměst. života, jeví jednak vlivy futurismu, jednak i jistou příbuznost s Ensorem a se snahami surréalistů. - Pro politický, zejm. antimilitaristický obsah karikatur byl [Grosz George] několikrát před soudem. 1932 byl z rozhodnutí studentů zvolen doc. kreslení na akademii v New Yorku. - Alba grafiky a karikatur: Erste Grosz-Mappe 1916, Kleine Grosz-Mappe 1917, Haifische 1920, Mit Pinsel und Schere (montáže 1920), Die Räuber 1922, Gott mit uns; Ecce homo 1923, Das Gesicht der herrschenden Klasse; Die Gezeichneten; Das neue Gesicht der herrsch. Klasse a j. - Obrazy: Německo, zimní pohádka 1918, Zatmění slunce 1925, portrety matky, spis. M. Herrmanna a W. Mehringa, boxera Schmelinga a j. Pro Piscatora inscenoval Haškova Švejka v Berlíně a nakreslil k němu řízné karikatury, které byly při představení promítány. - Srv.: Wolfradt W., George [Grosz George] 1921, Mynona, George [Grosz George] 1922, Italo Tavolato, Georg [Grosz George] 1924, Marcel Ray, George [Grosz George] 1927. Hs.

(In: Ottův slovník naučný nové doby)

1893

26. Juli: Georg Gross wird in Berlin als Sohn eines Gastwirts geboren.

1909

Aufnahme an der Königlichen Kunstakademie Dresden.

1912-1917

Er besucht mit Unterbrechungen die Kunstgewerbeschule in Berlin als Schüler von Emil Orlik (1870-1932).

1914

Um der allgemeinen Einberufung aufgrund der Wehrpflicht zuvorzukommen, meldet er sich bei Ausbruch des Ersten Weltkriegs als Freiwilliger bei einem Grenadier-Regiment in Berlin.

1915

11. Mai: Nach einer Operation einer Stirnhöhlenvereiterung wird er als dienstuntauglich entlassen.

1916

Namensänderung in George Grosz.

Mit der Veröffentlichung von Zeichnungen in der Monatsschrift "Neue Jugend" und in Theodor Däublers (1876-1934) literarischem Magazin "Die weissen Blätter" wird Grosz in der Kunstszene bekannt.

1917

4. Januar: Grosz wird als Landsturmpflichtiger erneut eingezogen.

20. Mai: Nach Aufenthalten in einem Lazarett für Schwerverletzte und einer Nervenheilanstalt wird er als dauernd kriegsunbrauchbar entlassen. Die "Kleine Grosz-Mappe" erscheint im Berliner Malik-Verlag.

1919

Verhaftung während des Spartakusaufstands. Aufgrund eines falschen Ausweises kann er jedoch entkommen und untertauchen.

Grosz wird Mitglied der Kommunistischen Partei Deutschlands (KPD).

1920

Erste Einzelausstellung in der Münchener Galerie "Neue Kunst Hans Goltz".

Mitveranstalter der "Ersten Internationalen Dada-Messe" in Berlin.

Heirat mit Eva Peter.

Grosz entwickelt sich zum Chronisten und Kritiker seiner Zeit. Vor allem der Militarismus und das konservativ-reaktionäre Bürgertum der Weimarer Republik sind Hauptthemen vieler seiner Gemälde und Mappenwerke.

1921

Anklage und Verurteilung zu einer Geldstrafe von 300 Mark wegen Beleidigung der Reichswehr. Das Gericht verfügt ferner die Vernichtung der Mappe "Gott mit uns".

1922

Fünfmonatige Rußlandreise mit Martin Andersen Nexö (1869-1954). Treffen mit Wladimir I. Lenin und Leo D. Trotzki.

1923

Die Erfahrungen in Rußland bestärken ihn in seinem Mißtrauen gegen jede Form der diktatorischen Obrigkeit und veranlassen ihn zum Austritt aus der KPD.

Aus der Mappe "Ecce Homo" werden mehrere Zeichnungen beschlagnahmt.

1924

Grosz und weitere sieben Küstler geben die Mappe "Hunger" zugunsten der "Internationalen Hungerhife" heraus.

1926

Zusammen mit Maximilian Harden, Max Pechstein und Erwin Piscator gründet Grosz den "Club 1926 e.V.", eine Gesellschaft für Politik, Wissenschaft und Kunst.

1928

Grosz fertigt 300 Zeichnungen für einen Trickfilm an, der während der Aufführung des Stücks "Die Abenteuer des braven Soldaten Schwejk" von Jaroslav Hašek (1883-1923) in Berlin zu sehen ist. Einige Blätter der gleichzeitig erschienenen Schwejk-Mappe "Hintergrund" führen zu einer Anzeige wegen Gotteslästerung.

1932

Mehrmonatiger Aufenthalt in New York.

1933

12. Januar: Grosz emigriert nach New York.

Gleich nach der Machtübernahme der Nationalsozialisten werden seine Wohnung und sein Atelier gestürmt.

1934-1936

Grosz arbeitet für amerikanische Satirezeitschriften.

1937

Die Nationalsozialisten diffamieren Grosz' Werke als "entartete Kunst" und beschlagnahmen 285 von ihnen aus deutschen Museen. Seine Bilder werden in der Ausstellung "Entartete Kunst" gezeigt.

1938

Grosz erhält die amerikanische Staatsbürgerschaft.

1941

Das Museum of Modern Art, New York, zeigt eine Grosz-Retrospektive.

1945

Beteiligung an der Ausstellung "Painting in the United States 1945" in Pittsburgh, auf der 350 Gemälde von 350 Künstlern gezeigt werden.

Grosz leidet unter depressiven Stimmungen, die zunehmenden Alkoholkonsum zur Folge haben.

1946

Grosz veröffentlicht seine Autobiographie "A Little Yes and a Big No" im Verlag Dial Press, New York.

1947-1953

Mehrere Ausstellungen in amerikanischen Museen.

1951

Erste Deutschlandreise nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg.

1954

Grosz wird Mitglied der hochangesehenen "American Academy of Arts and Letters".

1955

Grosz' Autobiographie erscheint als "Ein kleines Ja und ein großes Nein" im Hamburger Rowohlt Verlag.

1958

Die Berliner Akademie der Künste wählt ihn zum außerordentlichen Mitglied der Abteilung "Bildende Kunst".

1959

5. Juli: George Grosz stirbt kurz nach seiner Übersiedlung nach Berlin an den Folgen einer durchzechten Nacht. * * * * * "Grosz considered himself a propagandist of the social revolution. He not only depicted victims of the catastrophe of the First World War - the disabled, crippled, and mutilated - he also portrayed the collapse of capitalist society and its values. His wartime line drawings show him to be a master of caricature. In a 1925 portfolio of prints Grosz ridiculed Hitler by dressing him in a bearskin, a swastika tattooed on his left arm. Until 1927 he also painted large allegorical paintings that focused on the plight of Germany; Count Harry Kessler, a leading intellectual and collector, called these 'modern history pictures.'

"Grosz was called by some the 'bright-red art executioner,' and indeed his political radicalism was well known. He had joined the German Communist party in 1922. Although a trip to Russia later that year disillusioned him, he continued to work with [radical publisher] Malik Verlag. Feeling out of step with Russia's politics, Grosz resigned from the party in 1923, but the next year he became a leader of Berlin's Rote Gruppe (Red group), an organization of revolutionary Communist artists that prefigured the Assoziation revolutionarer bildender Kunstler Deutschlands (ASSO, Association of revolutionary visual artists of Germany).

"By 1929 the political climate in Germany had shifted to the right, and, at best, Grosz's work was considered anachronistic. The periodical Kunst und Kunstler (Art and artists) commented...: 'Dix's Barrikade (Barricade) and Grosz's Wintermarchen (Winter tale) are now curiosities that only have a place in a wax museum, commemorating the revolutionary time. One doesn't make art with conviction alone.' In a somewhat more positive light, Grosz was described as a historical figure in the periodical Eulenspiegel in 1931: 'No other German artist so consciously used art as a weapon in the fight of the German workers during 1919 to 1923 as did George Grosz. He is one of the first artists in Germany who consciously placed art in the service of society. His drawings...are worthwhile not only in the present but also are documents of proletarian revolutionary art.' These comments were more indicative of the magazine's editorial stance than the tenor of the times, however. More in keeping with popular sentiment, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration (German art and decoration) described Grosz as one-sided and pathological, 'too obstinate, too fanatical, too hostile to be a descendant of Daumier .' Although according to the magazine's art writer he was a master of form, his social point of view was wrongly chosen.

"Grosz's reputation as a political activist and deflator of German greatness was no secret. Menacing portents and premonitions of disaster began to haunt him. A studio assistant appeared in a brown shirt one day and warned him to be careful; a threatening note calling him a Jew was found beside his easel. A nightmare he recounted in his autobiography ended with a friend shouting at him 'Why don't you go to America?' When in the spring of 1932 a cable arrived from the Art Students League in New York, inviting him to teach there during the summer, he accepted immediately. After a short return to Germany, where he was advised that his apartment and studio had been searched by the Gestapo, who were looking for him, the artist emigrated in January 1933. He became an American citizen in 1938.

"In the meantime Grosz was among the defamed artists whose works had been included in two Schandausstellungen (abomination exhibitions) in Mannheim and Stuttgart in 1933 In a letter of July 21, 1933, Grosz wrote that he was secretly pleased and proud about this turn of events, because his inclusion in these exhibitions substantiated the fact that his art had a purpose, that it was true 9 The polemical articles about modern art, "art on the edge of insanity" as the official Nazi newspaper, the Volkischer Beobachter called it, also regularly included Grosz, with particular attention paid to his portraiture. A portrait of Max Hermann-Neisse, later to appear in the exhibition Entartete Kunst, was singled out for the "degenerate loathsomeness of the subject." A total of 285 of Grosz's works were collected from German institutions; five paintings, two watercolors, and thirteen graphic works were included in Entartete Kunst.

"Grosz participated in an anti-Axis demonstration in New York in 1940 and revealed his reaction to the Führer in an interview with Rundfunk Radio in 1958:

"When Hitler came, the feeling came over me like that of a boxer; I felt as if I had lost. All our efforts were for nothing."

"Grosz returned to Germany permanently in 1958, somewhat disillusioned with his American interlude. He had wanted a new beginning and had tried to deny his political and artistic past, but he was appreciated in America primarily as a satirist, and the work from the period after the First World War was perceived as his best. The biting commentary that marked this early work was that of a misanthropic pessimist, not what he had become: an optimist infatuated with the United States. Grosz was unable to understand the American psyche to the degree that he had the German, and he returned to his homeland in an attempt to regain the momentum he had lost. He died in Berlin in an accident six weeks after his return."

- From Stephanie Barron, "Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany" In: http://www.artchive.com/artchive/G/grosz.html * * * * * Born 26 July 1893 Berlin. Painter, writer and caricaturist. Studied at the Dresden and Berlin academies. Contributed to satirical periodicals. Came to the Berlin dada movement in 1918. Edited the periodicals "Die Pleite" ("Bankruptcy") together with Wieland Herzfelde; "Jeder sein eigener Fussball" ("Everyman his own Football") with Franz Jung; and "Der blutige Ernst" ("In Bloody Earnest"), with Carl Einstein. On his dada period he wrote in his book "Art In Danger": "Civilian again, I experienced in Berlin the rudimentary beginnings of the dada movement, the start of which coincided with the 'swede' period of malnutrition. The roots of this German dada movement were to be found in the recognation that it was perfectly crazy to believe that the spirit, or anything spiritual ruled the world. Dadaism was the only significant artistic movement in Germany for decades. Dadaism was no artificially fostered movement but an organic product, at its origin a reaction to the cloudlike ramblings of so-called sacred art. Dadaism forced artists to declare openly their position .. . What did the dadaists do? They said that it did not matter whether a man blew a 'raspberry' or recited a sonnet by Petrarca or Shakespeare or Rilke, whether he gilded jack-boot heels or carved statues of the Virgin. Shooting went on regardless, profiteering went on regardless, people would go on starving regardless, lies would always be told regardless—what was the good of art anyway? In those days we saw the mad final excrescences of the ruling order of society, and burst out laughing. We did not yet see that there was a system behind all this madness." George Grosz was the most pitiless caricaturist of the German bourgeoisie and of German militarism. In 1925 he approached that type of realism designated as "new matter-of-factness". In the U. S. A., where he went in 1932, his pictures assumed romantic, idyllic overtones. Looking back on it all, he wrote in his autobiography "A Little Yes And A Big No": "Artistically speaking we were 'dadaists' in those days. If that meant anything it was a disquiet, a dissatisfaction, a delight in mockery, that had all been fermenting a long time already. Every defeat, every upheaval gives birth to such movements. In another period we might have been flagellants . . . Huelsenbeck imported dada to Berlin, and it assumed immediately political features. The aesthetical side was preserved, but got more and more supplanted by a kind of anarchist-nihilistic politics, chiefly propounded by the writer, Franz Jung." In: http://www.peak.org/~dadaist/English/Graphics/grosz.html * * * * * 1893 Born: Berlin, Germany (July 26)

1908 Expelled from grammar school

1911 Königliche Kunstakademie. Dresden, Germany.

1912 College of Arts and Crafts. Berlin, Germany

1913 Trains at Colarossi's Studio. Paris, France.

1954 Elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters

1958 Elected to the Academy of Fine Arts of Germany

1959 Died: Berlin, Germany

Selected Exhibitions

1998 George Grosz-Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler, Galerie St. Etienne New York

1997 The Berlin of George Grosz: Drawings, Watercolors and Prints 1912-1930, Royal Academy of Arts London, England

1997 The New Objectivity, Galerie St. Etienne New York

1993 Art & Politics in Weimar Germany, Galerie St. Etienne New York

1986 German Realist Drawings of the 1920's, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum New York, NY

1985 German Art of the 20th Century, Royal Academy of Art London, England

1980 Expressionism: A German Intuition, S.R. Guggenheim Museum New York, NY

1978 Cityscape 1910-39: Urban themes in American, German and British art, Royal Academy of Arts London, England

1975 George Grosz, Leben und Werk, Kunstverein Hamburg

1959 Hecksher Museum, Hecksher Museum Huntington, NY

1954 Retrospective Exhibition, Whitney Museum of American Art New York, NY

1952 Dallas Museum of Fine Art, Dallas Museum of Fine Art Dallas, TX

1950 The Institute of Art, The Institute of Art Cleveland, OH

1948 The Stickmen, Associated American Artists New York, NY

1946 A Piece of My World in a World Without Peace, Associated American Artists New York, NY

1945 Associated American Artists, Associated American Artists Chicago, IL

1944 Denver Art Museum, Denver Art Museum Denver, CO

1943 Museum of Art, Museum of Art Baltimore, MD

1941 Associated American Artists, Associated American Artists New York, NY

1941 Traveling Retrospective Exhibition, Museum of Modern Art New York, NY

1939 Walker Gallery, Walker Gallery New York, NY

1938 Art Institute, Art Institute Chicago, IL

1937 Degenerate Art, Munich, Germany

1933 New York, NY

1933 Chicago, IL

1933 Philadelphia, PA

1932 Art Institute, Art Institute Milwaukee, WI

1931 Berlin, Germany

1931 New York, NY

1931 Chicago, IL

1930 Venice Biennale, Venice Biennale Venice, Italy

1930 Kunsthaus Zurich Zurich, Switzerland

1927 Flechtheim Gallery, Oils, Flechtheim Gallery Berlin, Germany

1925 Neue Sachlichkeit, Städtische Kunsthalle Mannheim, Germany

1920 First International Dada Fair, Berlin, Germany

1920 First One Man Exhibition, Hans Goltz Munich, Germany

In: http://www.artnet.com/artist/7477/george-grosz.html * * * * *

Grosz, George (1893-1959), American Expressionist painter and illustrator, of German birth. Born in Berlin, he studied art at the Royal Academy, Dresden, the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin, and the Académie Colarossi, Paris, and served in the army in World War I. He is known for his fiercely satirical drawings and caricatures. Collections of these drawings, concerned with conditions in Germany at the end of World War I, appeared in Ecce homo (Behold the Man, 1923) and Das Gesicht der Herrschenden Klasse (The Face of the Ruling Class, 1921). Republican Automatons (1920) reflects his view of modern man as a machine.

An uncompromising opponent of militarism and National Socialism, Grosz was one of the first German artists to attack Adolf Hitler. Grosz went to the United States in 1932 and became an American citizen in 1938. From about 1936 he began to work also in oils and turned to less biting themes, depicting nudes, still lifes and street scenes. With the approach of World War II his art became increasingly despairing. Recognized as one of the most brilliant draughtsmen of his time, Grosz was also well known as a teacher. An account of his experiences as an artist appears in his autobiography A Little Yes and a Big No (1946). He was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1954, and in 1959, shortly before his death, resettled in Berlin.

In: MS Encarta

Fotografie

|  |  |